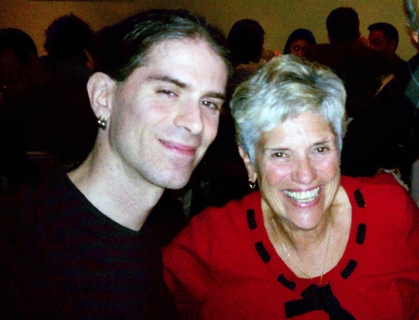

To celebrate the memory of Rutgers neurology professor Daniel Schneider, his mother, Penny Moreno, is ensuring his legacy lives on in future generations.

When Daniel Schneider, a fun-loving neurologist and psychiatrist, walked into M. Maral Mouradian’s office at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School to interview for an early-career professorship, Mouradian recognized him immediately. And it wasn’t just because of his signature long hair tied back in a low ponytail.

A few years earlier, in the middle of a flight home from Buenos Aires, Mouradian and Schneider, who were strangers at the time, both leapt into action when a fellow passenger began to have seizures. Though the plane was filled with physicians returning from the 14th International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Schneider stood out. “Dan was the one who stayed with the patient the longest,” Mouradian says, “taking genuine interest in providing care to a stranger.”

For that reason and many others, Schneider landed the job.

In his time at Rutgers—first as an assistant professor, then an associate professor in the Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry—Schneider established himself as an outstanding educator, a trusted adviser, and a caring clinician. He won numerous teaching awards and served as director of several neurology clinics.

Even when he became ill with pancreatic cancer in 2019, Schneider continued teaching, learning, and caring for more than a year until his death in February 2021 at age 46.

Now, thanks to three gifts totaling nearly $1 million from his estate, executed by his mother, Penny Moreno, Schneider’s legacy will live on at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and in the students who follow in his footsteps.

“I wanted to give back in his name and to support the department that supported him so much,” Moreno says. “I don’t want him forgotten. He was too young. He had too much potential.”

Fond Memories

From a young age, Schneider was fascinated with the human mind. After growing up in upstate New York, Schneider studied psychology in college. During his medical training at the State University of New York at Buffalo, Schneider became interested in movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease. That interest spawned a unique six-year medical residency for Schneider, who spent three years in neurology and three in psychiatry. He then completed a fellowship at Columbia University before finding himself in Mouradian’s office.

Many movement disorders have overlapping neurological, cognitive, and psychiatric manifestations, says Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut, chair of the Department of Neurology at RWJMS. “[Schneider’s] broad training endowed him with the skills to have a holistic approach to patients with neurodegenerative diseases.”

At the time of Schneider’s death, he was director of Rutgers’ clinics for deep brain stimulation, behavioral neurology, and functional neurologic disorders. “His loss was as impactful to us as to his family,” Dhib-Jalbut says.

A Patient Man

When Schneider’s illness forced him to be at home or hospitalized, often in great pain, he continued to meet with patients via telehealth appointments—a practice he continued until the month before his death. “When he got in front of that screen and he was treating patients, you didn’t know that there was a pain in his body,” says Moreno. “You could tell that was what he loved to do—to treat patients.”

Viewers of the Netflix series Diagnosis caught a glimpse of Schneider’s bedside manner in a 2019 episode. As a leading expert in functional neurological disorders, Schneider met virtually with a 44-year-old patient named Ann, who had unexplained paralysis and said previous doctors had frequently disbelieved her.

“I hear the frustration,” Schneider replied, leaning into the webcam. “I don’t have a vested interest in what the diagnosis is. I have a vested interest in getting people better. That’s really what I enjoy.”

Despite a demanding career, Schneider pursued a host of other interests.

He played several musical instruments and loved to dance, especially tango and swing. In 2013, Schneider was pictured in The New York Times dancing with friend Kiyomi Kubo at Lincoln Center’s Midsummer Night Swing event.

He held Latin poetry readings at his Manhattan apartment, which was packed with some 1,500 books. “He had every book imaginable,” Moreno says, “and read voraciously.”

Growing Minds

The gifts honoring Schneider will serve three distinct purposes, Moreno says.

An endowed early-career professorship in cognitive neurology will recruit and retain early-career scholars to serve as Rutgers faculty, just as Schneider had done.

An endowed lectureship in cognitive neurology will fulfill Schneider’s dream of a lecture series in his name—one that stimulates conversations and collaborations, allowing students and faculty to connect with leaders in the field.

And an endowed scholarship for Rutgers medical students interested in neurology will carry on Schneider’s legacy as an educator—one who won the Department of Neurology’s Teacher of the Year Award several times.

“I hope by the professorship, the scholarship, the lecture series,” Moreno says, “people remember.”