For Rutgers, addressing the youth mental health crisis—now exacerbated by the pandemic—is a top priority. Enter the Youth Behavioral Health Initiative, which provides innovative and equitable services to vulnerable young people across the state. And not a moment too soon.

One morning in May 2022, Devin* (her name and others in this article have been changed to ensure privacy), a journalist who covers health care, noticed that her 15-year-old son, Ajay*, was acting oddly. “He came out of his room, staggering,” she says. When asked, her son confessed to taking a dangerously large dose of cough medicine to get high. “He’d been experiencing anxiety and depression, but I had found him a therapist and a psychiatrist,” she says. “I thought I was doing everything right.” She called an ambulance, and as it arrived, she could clearly see that her son was intoxicated. “He was laughing, and the EMTs said his heart was racing,” recalls Devin. At the ER, the attending physician told her that Ajay was in the 99th percentile of the most depressed kids he’d seen and recommended that her son be admitted to the hospital. “Leaving him there was heartbreaking.”

While Ajay had struggled with his mental health since elementary school, the COVID-19 pandemic, says Devin, made her son’s challenges worse. “He always did better with social learning. Switching to remote was not a great set up for him,” she says. “He got more depressed, more removed, angrier.”

Ajay isn’t alone. The pandemic has exacerbated what was already an urgent mental and behavioral health crisis among young people. The reasons are many and varied, including sharp increases in bullying (in real life and online), pervasive violence in our culture (school shootings are now at their highest number in two decades), a growing sense of social isolation, and unrelenting academic and social demands. “It’s important to realize that youth mental health challenges don’t occur in a vacuum,” says Joshua Langberg, director of the Center for Youth Social Emotional Wellness at the Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology (GSAPP), clinical psychologist, and professor of psychology. “We have to take seriously that many young people, especially those living in poverty, feel marginalized and hopeless,” he says.

Worse, as rates of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other mental health disorders have skyrocketed among young people, resources to help them have not kept pace: “Even as our expectations of kids have increased, we haven’t taught them the social and emotional skills they need,” says Brian Chu, chair of the Department of Clinical Psychology at GSAPP and director of the Youth Anxiety and Depression Clinic.

The numbers tell the story. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the share of high school students who reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness jumped by 40 percent between 2009 and 2019, to more than one in three students. Worse, suicides in young people aged 10 to 24 increased by nearly 60 percent during the same period, making suicide the second leading cause of death among 15- to 24-year-olds. Substance use is also on the rise, including abuse of over-the-counter (OTC) medications. A 2018 study published in the journal Innovations in Pharmacy found that nearly half of OTC-related poisonings and emergency room visits by adolescents were because of misusing medication.

The numbers are worse among people of color and transgender individuals (also referred to as sexual and gender minorities among clinicians). They are more isolated, more likely to experience violence, and often have less access to resources they need.

Meeting an urgent need

Rutgers, a leading provider of mental health services, is uniquely positioned to help, providing affordable, equitable care for the most marginalized and vulnerable children, teens, and young adults. The university’s new Youth Behavioral Health Initiative—co-led by Rutgers–New Brunswick Chancellor-Provost Francine Conway; Frank Ghinassi, president and CEO of University Behavioral Health Care; and Langberg—harnesses the community outreach and training efforts of the Center for Youth Social Emotional Wellness and the adolescent and young adult treatment and prevention services of the new Brandt Behavioral Health Treatment Center and Residence at Rutgers. The Youth Behavioral Health Initiative will be the first in New Jersey to implement a holistic and comprehensive model for improving youth mental health outcomes, according to Langberg.

Devin, for one, found it daunting to identify a suitable treatment program for her teenager. “It has always been a challenge to find mental health care providers with expertise in treating young children and teens because so many graduate programs seem to focus on adult mental health, with child-focused study not fully integrated into required training,” says Kelly Moore GSAPP’09,’11, director of the Center for Psychological Services, a low-cost center at GSAPP that serves Rutgers students and other adolescents as part of the school’s community outreach.

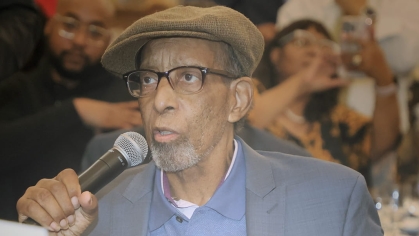

“Youth mental health challenges don’t occur in a vacuum. Many young people, especially those living in poverty, feel marginalized and hopeless.”

—Joshua Langberg, director of the Center for Youth Social Emotional Wellness

COVID-19 highlighted the problem of overwhelming demand for services—and too little supply. A 2019 study found that nearly half of the 7.7 million children and teens in the United States with at least one treatable mental health disorder weren’t getting the care they required. Then came COVID-19. As the need for quality mental health care climbed among young people, access to those services plummeted.

“When COVID hit, it was gasoline on a fire,” says Jennifer Foster GSAPP’10, an assistant teaching professor at GSAPP and director of the Multi-Tiered Systems of Support programs. “Before, kids at least had access to community services and their Monday-to-Friday school routine,” she says. “As communities shut down, all of that went away.” The lack of routine during the pandemic left many children and teens with almost unlimited access to social media as parents struggled to find childcare or adjust to working at home. “During the pandemic, my 10-year-old son, Jordan*, was depressed, and he began spending a lot of time on video games,” says Alonzo*. “I let it slide because I figured that at least he was talking to other kids online.”

His son then migrated to TikTok and began posting disturbing things, including a video of himself beating up a stuffed animal. When Alonzo tried limiting Jordan’s phone use, Jordan attempted suicide, downing a bottle of ibuprofen. “We ended up spending three nights in the local ER because there were no beds in any inpatient psychiatric units for a child his age,” Alonzo says. “Programs usually start for kids who are 12 or 13.”

Foster, a former district school psychologist for the Perth Amboy Public Schools in New Jersey, has heard countless stories like this. “I think of COVID as a tsunami: it swept everything away and then, suddenly, we were all plunged back into life. Many school and community support systems were quickly overwhelmed,” she says. “We’d send kids out for screenings, and they would have to wait hours to be seen, or sometimes they’d sit in emergency rooms for days because there were no beds. The magnitude of the need was tremendous.”

Addressing deep disparities

Mental and behavioral health needs are particularly acute for families of color who are already underserved, leading to a domino effect of crisis upon crisis. In 2021, 31 percent of Black and Hispanic youth in New Jersey lived in poverty compared to 11 percent of white and Asian youth. “In the pandemic, people of color had higher death rates, which created more emotional and physical health problems as well as economic problems related to losses of jobs and caregivers,” says Chu.

Moreover, the most vulnerable families have greater difficulty accessing even the most basic mental health care for their kids. “You have to know what mental health concerns look like and have an idea of what type of service provider to call,” says Langberg. “You also need transportation to get to that provider and to be able to pay for services.” And it’s the rare practitioner who looks like a child of color: in 2019, the American Psychological Association found that only 3 percent of psychologists nationwide were Black.

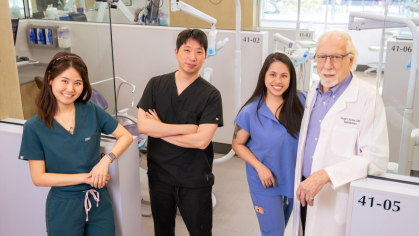

The inequities are just one of the structural and systemic barriers to care that the Rutgers Youth Behavioral Health Initiative is addressing. “It approaches mental health care more holistically by bringing different perspectives and types of expertise to the table,” says Langberg. That means not only training more therapists, but also recruiting and training a more diverse group.

“We are immensely proud of this initiative, which is providing mental and behavioral health care and support for adolescents and young adults in New Jersey and throughout the Northeast while fostering innovation and learning,” says Conway, a licensed clinical psychologist. “Our aim is to use the research engine of Rutgers to forge interdisciplinary teams that can address the region’s mental health treatment desert, solve grand challenges, and serve the public good.”

Serving the public good also means broadening the definition of what diversity means. “Rutgers and GSAPP are working to rapidly diversify the mental health workforce, training clinicians from underrepresented backgrounds, who speak more than one language, and who are ‘neurodiverse,’” says Langberg of practitioners who themselves live with conditions such as autism and ADHD. And making sure to include LGBTQ+ therapists is also crucial because this population often has difficulty accessing the care they need.

“It has always been a challenge to find mental health care providers with expertise in treating young children and teens.”

—Kelly Moore, director of the Center for Psychological Services

“These kids have been under stress for a long time. The demands on them have increased and the expectations have increased,” says Chu. “That’s why we need to take a more comprehensive approach.” That approach, he says, should include normalizing regular mental health checkups for kids at the pediatrician and in schools. “That’s a critical way we can identify and help young people who need help early.”

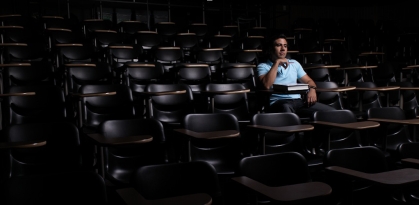

Fifteen-year-old Alex* was among them. When the transgender teen began struggling with feelings of isolation, anxiety, and depression in elementary school, he didn’t know where to turn. “For a long time, I felt I was different, that I didn’t feel comfortable in my body, and it got worse when I started getting breasts. I was, like, ‘This isn’t OK!’ But I didn’t even know that trans people existed,” he says.

To make matters worse, just before the pandemic kicked in, most of his friends at school began to shun him. “Then in-person school ended, and I felt even more lonely and stressed,” he recalls. “I was hit by huge waves of anxiety.”

Alex’s parents knew he needed help—and quickly. A 2022 study in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence found that 80 percent of transgender youth have thought about committing suicide, and 40 percent have attempted to do so. “Before the pandemic, we started an intensive outpatient program for young adults with anxiety and mood disorders,” says Helen Paulucci, a mental health clinician and social worker. She addresses addiction with the Specialized Addiction Treatment Services program, part of Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care. The program offers an extensive range of mental health services for youths and people of all ages. Paulucci was struck, she says, by how many attendees of the outpatient program were LGBTQ+. “Seventy percent were LGBTQ+, a portion of whom were transgender young adults,” she says.

Yet, for Alex’s parents, finding a therapist who had experience working with trans teens was tough. “One therapist admitted that she had never worked with anyone in the trans community,” says Alex’s mother. “It was almost as if she was trying to learn from him, rather than the other way around.”

However, training more practitioners who can meet the needs of diverse patients is only part of the solution. The great need can be met only with the help of the community, Langberg and other experts at Rutgers agree. “We, the experts, must go where problems are most likely to be identified—schools, pediatricians’ offices, and community organizations,” he says. “We need to work together with providers in these settings so they can implement evidence-based assessments and prevention practices, and know when and how to connect with a psychologist if necessary.”

A community-based approach

There’s no time to waste. While the typical gap between someone showing signs of a mental health disorder and seeking treatment is about 11 years, kids and families will meanwhile encounter others in the community and schools who can potentially help them. “Part of how we address this shortage of practitioners amid the youth mental health crisis is to make sure we alert the public about the signs and symptoms that someone is struggling,” says Moore. “I’ve trained law enforcement, educators, church staffers, and scout troop leaders—the people who interact with children. They need to know how to ask the right questions.”

One way to help them do that lies in GSAPP’s multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) programs. GSAPP offers specialized MTSS training that teachers, support staff, and administrators can use to develop strong prevention and intervention programs. “With a tiered system, schools can begin to address mental health concerns by adopting programs that build foundational skills in social emotional learning (SEL) for all students,” says Foster. MTSS can be a highly effective and equitable way for schools to organize their SEL and mental health services and programs.

The premise of a tiered system is to identify when students need additional classroom support or when they struggle despite school-wide prevention efforts. For example, when students need more help with regulating their emotions, they can access services that use small groups to teach self-awareness and self-management skills. If kids continue to struggle, they can access more intensive Tier 3 services, which might include direct services such as individualized therapy. “That might mean seeing a school psychologist or working with a community agency to set up therapeutic interventions,” says Foster.

“I talk to a lot of parents who feel guilty, who tell me they wish they’d noticed the problems sooner, but parents can always intervene.”

—Brian Chu, director of the Youth Anxiety and Depression Clinic

Children can also benefit from the data gleaned from regular and early screening for social emotional learning and mental health concerns. “Schools implementing a MTSS framework can then use this information in a systematic way to develop programming to meet the needs of a district, school, classroom, or individual student,” says Foster. “In doing so, schools provide students with equitable access to supports and avoid duplicating services, a must when school districts are already stretched thin.”

The in-school, in-community programs supported by Rutgers research and science give experts like Moore hope. “Kids are in school every day; having school-based mental health services is a huge way to tackle the problem of access.”

These kinds of partnerships are essential, especially now, and Rutgers already has some in place—and is building on that solid foundation. “The community needs to drive the mission,” says Langberg. “We have to stop assuming we have all the answers— and start listening.”

Listening to kids is also crucial in recognizing when they might need help. Alex, who is now seeing a therapist and psychiatrist he likes, is grateful that his parents listened to his concerns and wishes more adults would do the same. “So many adults see children as ‘less than,’” he says. “They assume that if a kid is upset about something, they’re just overreacting. But that’s not the case.”

Devin’s son, Ajay, is back in school, and she has had promising leads on programs that might work for him. Despite the huge challenges, Devin feels lucky that she has resources to keep pushing to find the right help for her teen. “I have excellent health insurance and my parents also help,” she says. “But knowing what I know now, I’m really scared for my kid.”

Chu says it’s never too late for parents to act. “I talk to a lot of parents who feel guilty, who tell me they wish they’d noticed the problems sooner, but parents can always intervene,” he says. “Rutgers is really investing in young people and mental health. The time to act is now.”

Support the Initiative

Help provide world-class behavioral health care to young people in New Jersey and the region, regardless of their families’ income.