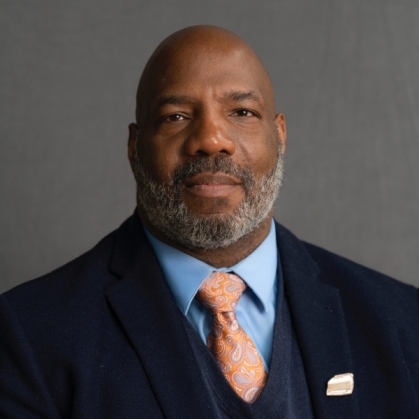

Jelani Cobb: What I Know Now

Through his books, New Yorker articles, and teaching and serving as an administrator at prestigious universities—including Columbia University, where he is dean of the Graduate School of Journalism—Rutgers alumnus Jelani Cobb is a leading voice in the national conversation on how race, politics, history, and popular culture intersect in America. In his own words, Cobb shares his story about the twists and turns of his lifelong love of learning.

From attending elementary school in Queens to storming the administration building at Howard University to earning his doctorate at Rutgers University and serving as dean of the journalism school at Columbia University, Jelani (which means “strong, powerful”) Cobb has blazed a trail of accomplishment. His father, an electrician with a third-grade education, taught him how to write, and his mother inspired him by earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in her fifties. That gift of education was one he has been compelled to share with others, by writing books on history and culture, penning articles for the New Yorker, and by teaching and serving as an administrator at the University of Connecticut, Spelman College, Rutgers, and Columbia. In his own words, Cobb shares his story about the twists and turns of his lifelong love of learning.

‘Read until it closes’

It was drilled into my three siblings and me that education was key to us being able to live the lives we wanted to live. I went to this perfectly balanced high school in terms of demographics. There was tremendous social and cultural diversity. What I didn’t know at the time was how important learning to operate in multicultural environments and interact with people from differing backgrounds would be.

After high school I enrolled at Howard University but only took classes when I had money, so it took me seven years to finish my undergraduate degree—something I was tremendously embarrassed of for a long time, until I realized how it equipped me to relate to students who are in that position now.

When I was finishing my degree at Howard, the first volume of David Levering Lewis’s biography of W.E.B. Du Bois came out—it was around 700 pages long and I devoured it. I became a low-grade stalker and wanted to know everything about David Levering Lewis. I was astounded that someone could write something that magisterial, erudite, and graceful.

With my bachelor’s in English, I knew I wanted to get a Ph.D. in history. People were shocked: It took you seven years for a bachelor’s—how many more years to get a Ph.D.? I jokingly said I did everything I could do to reasonably avoid making any money. But I didn’t want to be deterred, so I applied to the Rutgers joint master’s/Ph.D. program where David Lewis was teaching. And it took me seven years to complete it.

Rutgers, to me, is the model of what a state university should be. It is woven into the lives of every single resident of New Jersey in some way, shape, or form. Many state universities just happen to be in that state, and if you picked them up and put them in a different state, they would still be pretty much the same. But Rutgers has a keen connection to the residents. It is of New Jersey, not just in New Jersey.

There are only three people in life whose approval I’ve ever sought—my mother, my father, and David Levering Lewis. David gave me a piece of advice, which I followed to the letter. He told me to go to the library when it opened. I was thinking he’s going to give me some ornate complicated set of research instructions, but he just said: Read until it closes. I considered that to be my marching orders.

When I received my Ph.D. from Rutgers my mother was seated 12 rows up from the floor. I gave my diploma to a person in the first row and told them to pass it back. They passed it back and passed it back and it went all the way up the rafters until it got to her. I gave her my diploma and never took it back. It was an intergenerational gesture. I was trying to get all the education she’d been unable to receive growing up in the Jim Crow South.

‘I hope this works out'

I played high school baseball with a kid whose parents had met at Howard University and his father encouraged me to go to there. I had never visited—I just showed up and was like, I hope this works out.

Howard was politically charged in the 1980s, so our education was driven by a bigger ethic than how much money we could make when we graduated. Violence [was on the rise] in American cities, particularly [Howard’s home] Washington, D.C.—the murder capital of America at the time. Crack was driving a lot of the violence. HIV/AIDS was decimating communities. Abroad, we were seeing things like apartheid in South Africa. We had a responsibility to try to tackle these problems.

In the 1988 presidential election, George H.W. Bush’s campaign had the famous Willie Horton ad with obvious racial implications. Weirdly enough, the next year, Howard’s president [James E. Cheek] appointed Lee Atwater, who had been Bush’s campaign manager and had okayed that ad, to the board of trustees, which we couldn’t understand. It spread like wildfire around campus that we should occupy the administration building. So, in March 1989, we marched into the building, locked ourselves in, and launched a protest that generated national headlines. Before we knew it, journalists were asking President [George W.] Bush about the protest during White House briefings. After three days, Lee Atwater resigned from the board. It was important for us to learn that we could influence what happened in the world. Howard has a long tradition of being an activist-oriented, raucous, political student body. People from a 1968 protest came to campus in 1989 and advised us. Two years ago, when students took over again, people from 1989 came to campus and talked to them.

It isn’t hard to see how terrible things are when you look at the headlines. But every single day, I do something that I think makes the world a little bit better—in terms of teaching, of being a historian, of being a journalist, and now being a dean. It is a privilege to do any of those things.